* Copy courtesy of Pantera Press *

Soon murder proves that fear well founded.

When Rowland receives word of Cartwright’s death, he sets out immediately for Boston, Massachusetts, to bury his friend and honour his last wishes. He is met with the outrage and anguish of Cartwright’s family, who have been spurned in favour of a man they claim does not exist.

Artists and gangsters, movie stars and tycoons all gather to the fray as elite society closes in to protect its own, and family secrets haunt the living. Rowland Sinclair must confront a world in which insanity is relative, greed is understood, and love is dictated; where the only people he can truly trust are an artist, a poet and a passionate sculptress.

Appointed executor to the will of his former Oxford classmate and lifelong friend, Danny Cartwright, Rowley and his team travel to Boston, Massachusetts and land, quite predictably, in trouble. Danny’s homosexuality and murder offer an immediate and compelling justification for Gentill’s historical backgrounding. Between the rise of the Italian gangster mobs, the bitterness of family inheritance disputes, burgeoning anti-semitism in the shadow of rising Nazism and the aftermath of the stock market crash of 1929, it is a rich and timely location for a novel that affords more than a nod to the noir fiction of the period.

Utilising her familiar leavening of local newspaper extracts from the period to introduce, anticipate or lubricate her plot development, Gentill’s team of Australians sleuth their way, sometimes violently, towards the expected resolution. In transit, they encounter flaming family jealousies, bitter broken romances and brutally homophobic efforts to suppress the realities surrounding Danny’s will.

The role of corruption in law and politics, the employment of the asylum to contain embarrassing relatives, the reluctance of Americans to engage with growing international tensions are all too familiar but absolutely engaging in Gentill’s hands. In this probably ‘post-Trumpian’ period, A Testament to Character appears prescient but we have had four years to become accustomed to the extremes.

Intro

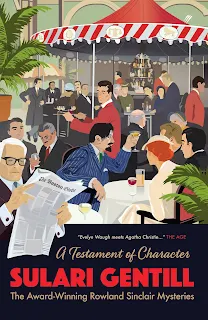

A Testament of Character is the tenth book in the Rowland Sinclair Mysteries by Australian author Sulari Gentill. Set in the 1930s, Rowland Sinclair is an artist and a gentlemen, and guest reviewer Neil Béchervaise had this to say about the book.Blurb

In fear for his life, American millionaire Daniel Cartwright changes his will, appointing his old friend Rowland Sinclair as his executor.Soon murder proves that fear well founded.

When Rowland receives word of Cartwright’s death, he sets out immediately for Boston, Massachusetts, to bury his friend and honour his last wishes. He is met with the outrage and anguish of Cartwright’s family, who have been spurned in favour of a man they claim does not exist.

Artists and gangsters, movie stars and tycoons all gather to the fray as elite society closes in to protect its own, and family secrets haunt the living. Rowland Sinclair must confront a world in which insanity is relative, greed is understood, and love is dictated; where the only people he can truly trust are an artist, a poet and a passionate sculptress.

Neil's Review

Sometimes we forget, sometimes we never knew, that the United States of today, the land of dreams and extremes, of bullying, racism, capitalism, unionism and film stars, is nothing new. It is, after all, the spawning ground of Raymond Chandler, Errol Flynn, Randolph Hearst and the Ku Klux Klan. Sulari Gentill’s 10th novel featuring Australian Rowland Sinclair, however, brings the realities of 1935 east coast America into unexpected and graphic focus.Appointed executor to the will of his former Oxford classmate and lifelong friend, Danny Cartwright, Rowley and his team travel to Boston, Massachusetts and land, quite predictably, in trouble. Danny’s homosexuality and murder offer an immediate and compelling justification for Gentill’s historical backgrounding. Between the rise of the Italian gangster mobs, the bitterness of family inheritance disputes, burgeoning anti-semitism in the shadow of rising Nazism and the aftermath of the stock market crash of 1929, it is a rich and timely location for a novel that affords more than a nod to the noir fiction of the period.

Utilising her familiar leavening of local newspaper extracts from the period to introduce, anticipate or lubricate her plot development, Gentill’s team of Australians sleuth their way, sometimes violently, towards the expected resolution. In transit, they encounter flaming family jealousies, bitter broken romances and brutally homophobic efforts to suppress the realities surrounding Danny’s will.

The role of corruption in law and politics, the employment of the asylum to contain embarrassing relatives, the reluctance of Americans to engage with growing international tensions are all too familiar but absolutely engaging in Gentill’s hands. In this probably ‘post-Trumpian’ period, A Testament to Character appears prescient but we have had four years to become accustomed to the extremes.

This novel reminds us that there is little that is new – in fact any more than in fiction.